Chancellor Friedrich Merz (CDU) has proposed capping housing costs for recipients of Germany’s citizen’s benefit(“Bürgergeld”) as part of a broader reform of the country’s basic social security system. Speaking in an ARD “Summer Interview” on Sunday, Merz argued that the current subsidies are often too high and require urgent review.

“In some major cities, recipients are getting 20 euros per square meter. For 100 square meters, that’s 2,000 euros a month, a normal working family can’t afford that,” Merz said. He suggested introducing flat-rate payments, lower reimbursement rates, and stricter limits on apartment sizes eligible for state support. The chancellor added that the planned reform, which would replace the citizen’s benefit with a new basic welfare system starting next year, could bring “significant savings.” He noted, “There’s more to be saved than just one or two billion.”

Merz also stressed that the changes would be gradual and involve ongoing adjustments to ensure fairness and efficiency. “The goal is to make sure those who truly need state aid continue to receive it,” he said. At the same time, Merz criticized individuals “who can work but don’t, or only work part-time while doing illegal jobs,” calling this a flaw in the current system.

✅ A standard needs rate for essential daily expenses.

✅ Reasonable housing and heating costs, provided these are not covered by income or assets.

✅ Additional allowances in special cases, such as for single parents, pregnant women, or those requiring special diets for medical reasons.

In short, Bürgergeld is intended as a safety net for people without employment or with incomes too low to meet basic living costs. It replaced the Hartz IV system in 2023 and is administered by Jobcenters across Germany.

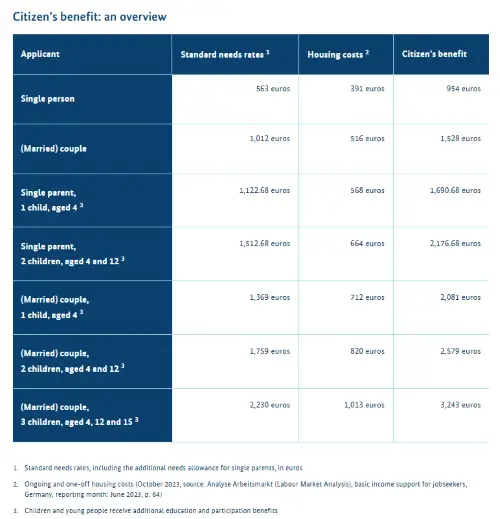

Currently, around 5.4 million people in Germany rely on Bürgergeld to cover their basic living expenses. Of these, approximately 2.7 million are not active in the labor market because they are unable to work, engaged in education or vocational training, or providing care work. Another 830,000 individuals receive supplementary benefits because their wages are too low to sustain a decent standard of living. Meanwhile, about 1.9 million Bürgergeld recipients are unemployed. In total, Germany spends roughly 52 billion euros annually on basic income support, with 29 billion euros allocated specifically for Bürgergeld payments. The federal government contributes €13 billion to cover housing and heating costs.

When calculating Bürgergeld, job centers cover reasonable housing expenses. Local authorities determine what is “reasonable” based on regional guidelines for social housing, setting limits on floor space, rent, and utilities.

If housing costs exceed these limits, claimants are typically asked to reduce expenses within six months. Since January 2023, a “grace period” was introduced: during the first year of receiving Bürgergeld, actual housing costs are covered in full.

If implemented, the reform could bring major changes for Bürgergeld recipients:

For many, the reform raises concerns about increasing financial insecurity, especially in cities where rents are already unaffordable.

Merz’s proposal sparked immediate backlash from across the political spectrum and civil society. SPD deputy parliamentary group leader Dagmar Schmidt rejected the idea, warning that cutting housing benefits could worsen homelessness without solving the root problem of soaring rents. “Housing for average earners won’t become cheaper by cutting support for those on social benefits,” Schmidt said.

The Green Party’s housing spokesperson, Kassem Taher Saleh, accused Merz of targeting vulnerable groups while failing to offer concrete solutions for affordable housing. “Millions of people are already struggling to pay rent and now face even more insecurity,” Saleh said. The Left Party’s Ines Schwerdtner called Merz’s approach a “classic reversal of the perpetrator-victim relationship,” arguing that high rents, not social benefits, are the real issue.

The German Tenants’ Association criticized Merz for focusing on cutting benefits instead of tackling skyrocketing rental prices. “The state should set effective limits on landlords and ensure affordable housing,” said Association President Melanie Weber-Moritz.

Verena Bentele, president of the social association VdK, warned that existing housing cost caps are already too low for most markets. “Many families on citizen’s benefit are forced to pay part of their rent from their standard income, leaving even less money for food or electricity,” she said.

Despite the criticism, Merz defended his plan as a necessary measure to restore balance and fairness in Germany’s welfare system. He argued that reforms would help reduce tensions between welfare recipients and working families.

Federal Labor Minister Bärbel Bas (SPD) intends to present a draft proposal for reforming the citizen’s benefit system after the summer break. As confirmed by Chancellor Friedrich Merz, the reform, anchored in the coalition agreement, is set to take effect in 2026. Merz also indicated that broader discussions on Germany’s social security systems are expected this fall, highlighting concerns about the state’s financial sustainability. The level of social security benefits will also be part of these debates.